The “misuse doctrine” relates to when someone attempts to use IP licenses to obtain rights beyond the scope of their statutory IP right. In the case of patent law, it provides a remedy against attempts by the patent holder to unjustly expand their “monopoly” right. Misuse is sometimes raised as a defense to an IP infringement claim where the alleged says that the patent holder misrepresented their rights. A finding of misuse for a patent holder can be devastating to their monetization efforts. If misuse is found, the patent is rendered unenforceable until the misuse is “purged”. The difficulty proving “misuse” is that the “boundaries” of a patent right are hard to interpret during license negotiations. The terms used in licensing agreements are often not the same terms used in the patent itself. Since it is in the patent holders best interest to interpret their patent as broad as possible they will use terms that push the limit of these ‘boundaries’ and claim that they are within the scope of a patent.

A common example of misuse involves the “tying” of both patented and non-patented rights—that is, the patent holder claims payment is due for the rights to non-patented IP licensed in connection with their patented IP.

Over the past year, the mobile marketing industry has been impacted by many patent infringement suits. One of which I am aware of may have involved patent misuse. A company by the name of Helferich Patent Licensing (HPL) has been sending letters to companies demanding licensing fees for their patent portfolio. The patent portfolio in question is built around the concept of sending web links within SMS text messages. They are a typical “Non-Practicing Entity” who does not build any products and is in the business of extracting licensing fees from companies for use of their intellectual property rights. Although the SMS industry started many years earlier than 2005, most of their asserted SMS patents were filed in 2005 or later. These patents are all continuations or divisional patents which expand the scope of a parent patent filed in 1997 relating to voicemail (Patent 6,233,430). This “continuation” classification gives Helferich the ability to act as if they invented these 2005 patent claims back in 1997 and sue companies for it. However ridiculous this sounds, this is the current state of how our patent system works. The validity of the HPL patent claim continuations and divisional patents are currently being re-examined by the USPTO on behalf of a handful of companies who were sued by HPL. These companies believe that the claims within the continuation patents were either invalid based on prior art or that the expanded scope from the original 1997 voicemail patent was incorrectly allowed. I will not comment on their validity in THIS blog post as I have a lot to say about that as well. In my next blog about HPL Patents, I will talk about their invalidity from a technical perspective.

HPL has successfully pressured hundreds of companies into settlements for hefty fees. Helferich is asking for a payment of 2 cents per message for ANY SMS delivered to a phone which contains a URL. This fee is far beyond reasonable and fair terms as the fee is more than the cost the entire value chain charges per message which is why many companies have decided to fight. These larger companies who could afford litigation are currently disputing these HPL patent demands in court. Smaller companies, without the resources to litigate, have been compelled to act against their will and sign agreements for HPL’s broad interpretation of their patents rights in order to satisfy the contractual indemnification provisions with their customers.

What I believe to be an example of misuse and potential inequitable conduct is that HPL’s patent rights specifically limit the scope of their invention to systems where ONLY the URL is contained in the SMS. They are currently asserting their patents cover systems where ANY URL is contained in the SMS. This seems to be an example of “tying” non-patented rights to their own rights and collecting license fees for it. In normal circumstances, their interpretation could be disputed. However, in the case of HPL, the limits and ‘boundaries’ of their patents were clearly known to them as they had to argue these limits with the patent examiner just to get their original parent patent approved in 1997. In other words, they may have been litigating and collecting license fees for an invention which was specifically denied to them by the USPTO.

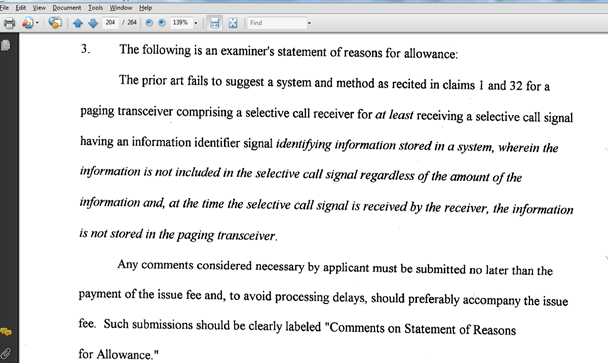

Back in 1997 when HPL filed the parent voicemail patent (6,233,430) they were rejected twice by the examiner. The information about these rejections is only available in the 6,233,430 Patent File History and is not available in the actual Patent document you can view online. The examiner found that another patent (5,448,759) by Krebs et al. explained the very same thing as prior art. Helferich argued that his patent was valid because it claimed that “the information is NOT included in the selective call signal regardless of the amount of information”. This statement eventually led to the USPTO approving their patent (Page 204). What this means is that the parent invention scope is explicitly limited to systems where the “selective call signal”, or the “SMS message”, ONLY contains a link and no other information.

When their asserted continuation Patents were first re-examined by the USPTO the original claims were rejected because patent examiner had mistakenly approved the continuations with a broader the scope than the parent application (among other things). The rejected claims were later modified by Helferich and approved by the USPTO as amended. If you take a look at patents such as 7835757, 7499716 , 7280838, we can notice that they have B1 or B2 which symbolize that they were reissued with changes after a re-examination proceedings. If you read them carefully you can see that HPL was required to add words to their claims like “wherein the information is not included in the data” or ”wherein the content is not included in the message” which were the claim boundaries in their parent patent.

HPL continues to claim that their re-issued patents are in the same substantive form as originally issued with minor clarifying amendments. If they continue to demand payment from companies and licensees for any text messages that contain a link then I believe they are they ‘tying’ rights to a content delivery technology that was explicitly denied to them by the USPTO.